I'm always fascinated by the ability of modern off-the-shelf components to bring levels of performance and

functionality to my home workbench that were previously seen only in laboratory environments and high-

budget military/industrial settings. Every time Mini-Circuits

announces a new line of parts, Digi-Key adds

another 200 pages to their catalog, or the electronic-component categories on eBay double in size once

again, I find myself thinking, "There's got to be a free lunch in there somewhere."

I'm always fascinated by the ability of modern off-the-shelf components to bring levels of performance and

functionality to my home workbench that were previously seen only in laboratory environments and high-

budget military/industrial settings. Every time Mini-Circuits

announces a new line of parts, Digi-Key adds

another 200 pages to their catalog, or the electronic-component categories on eBay double in size once

again, I find myself thinking, "There's got to be a free lunch in there somewhere."

Well, here's one of those (almost-) free lunches. With a couple of inexpensive ECL line receiver chips and monolithic amplifiers that are probably already in your parts drawer, you can build a comb generator -- a versatile signal source that can help you align receivers, test antennas, or synthesize local-oscillator signals at frequencies from a few dozen MHz to 10 GHz.

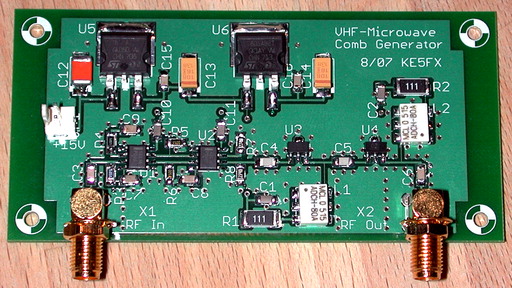

Download: All project files created with CadSoft EAGLE 4.16r2

Download: Four-layer Gerber and drill files only, suitable for submission to BatchPCB.com

What's a comb generator?

There's nothing new or exotic about comb generators, and it's not hard to imagine what they do. Given an input signal at a relatively-low frequency, and a spectrum analyzer on which to view the output signal, a comb generator's output consists of a series of harmonics of the input signal that usually stretch well into the gigahertz range. In the time domain, the impression is that of a chaotic yet repetitive waveform composed largely of very fast edges -- so fast that an equivalent-time sampling oscilloscope may be needed to appreciate the signal in detail.

Above: 1-GHz comb harmonics from hand-wired prototype

Left: FR-4 PCB output waveform with 100 MHz input, via Tektronix 7S11 sampler. Photo courtesy of Dennis Tillman

What's awkward about building comb generators and other broadband multipliers is that they're

traditionally based on exotic components such as step-recovery diodes (SRDs) or

nonlinear transmission-line devices (NLTLs). SRDs have previously seen application in the Amateur microwave community.note 4

They're difficult to source as new components, though, since their exotic nature and limited commercial

applications have kept them out of the catalogs of the major retail parts distributors. Advanced Semiconductor, the only SRD vendor

I've been able to work with directly, has a US $250 minimum order for their ASRD 800-series parts. So when I needed a comb generator for

a project recently, it made sense to look for alternatives.

Circuit Notes

Any active or passive device with nonlinear gain characteristics will generate harmonic distortion in some form. My design uses a series of four cascaded active devices, each of which can provide gain from DC through several GHz. Harmonic generation occurs as a consequence of deliberately overdriving the active devices.

The first two stages consist of MC100EL16D differential line receiver ICs from ON Semiconductor. These chips are designed to condition low-level analog signals for introduction into a fast ECL logic environment. As such, they exhibit significant gain, not unlike a comparator without hysteresis. (In fact, self-oscillation in the absence of an input signal is normal.) The input impedance at U1 is 50 ohms, as is the nominal output impedance at U2 with the chosen values of R7 and R8. (See notes 7 and 8 below for links discussing impedance-matching issues with ECL.)

With a rated toggle frequency of 1.75 GHz and output edge speeds in the 100-300 ps range, the ECL line

receivers are fast enough to serve as useful harmonic sources by themselves. Their differential input stages

are great at isolating the output waveform's characteristics from those of the input signal, a very desirable

trait in a comb generator. However, the output harmonics fall off more rapidly than desired, and the even-order harmonics are somewhat underrepresented.

With a rated toggle frequency of 1.75 GHz and output edge speeds in the 100-300 ps range, the ECL line

receivers are fast enough to serve as useful harmonic sources by themselves. Their differential input stages

are great at isolating the output waveform's characteristics from those of the input signal, a very desirable

trait in a comb generator. However, the output harmonics fall off more rapidly than desired, and the even-order harmonics are somewhat underrepresented.

Right: Output signal from two cascaded MC100EL16 ECL line receivers, driven at 33 MHz

The circuit presented here achieves improved performance in both respects by following the ECL line receivers with two inexpensive MMIC amplifiers. The monolithic amplifiers are undercoupled with 1-pF capacitors in an attempt to equalize lower- and higher-frequency harmonic generation. My device of choice was the Mini-Circuits GALI-5+, which exhibits about 16 dB of gain at frequencies up to 4 GHz and is still usable at twice that frequency. By combining these two different device types, we can take advantage of the input-level independence offered by the ECL line receivers and the superior harmonic-generation characteristics of the MMICs.

Results and Measurements

Among the many applications for a comb generator is as a driver for a harmonic mixer or sampler. These devices, in turn, find wide application in equipment from synthesizers to network analyzers. My own intended use for the comb generator required specs similar to those of the SRD-based generator in the popular HP 8753A/B vector network analyzer, so it proved helpful to compare the performance of my own circuit to that of its counterpart in my HP 8753A during development.

Below: 30-MHz harmonics from HP 8753A internal SRD source. Difference between strongest and weakest harmonics is 26 dB

One useful performance metric for a comb generator is the differential amplitude of the strongest comb harmonic and the weakest. Within a given output range, this parameter tends to improve with increasing drive frequency, so measuring it at 30 MHz does a good job at representing worst-case results. The HP 8753A's generator is excellent in this regard; only 26 dB separates the weakest comb tooth (at approximately 1400 MHz) from the strongest, near 750 MHz. Shown here is the output spectrum from the HP 8753A's comb generator at 30 MHz; results at 60 MHz are similar. Under identical test conditions, my ECL/MMIC generator yields good results as well, but not as good as the far-more-complex and -expensive Hewlett-Packard design.

Below: 30 MHz harmonics from KE5FX comb generator. Difference between strongest and weakest harmonics is 37 dB

Like my own circuit, the HP 8753A's internal comb generator incorporates cascaded ECL line receivers at its

input, although this 1980s-vintage instrument uses the older (and slower) MC10116. Next, a cascode

preamplifier stage drives an emitter-follower PA based on three parallel 2N5109s, with the step-recovery

diode in the emitter return path. Extensive additional circuitry, including three more 2N5109s, is used to

optimize the SRD drive waveform at lower input frequencies. An input filter limits the drive frequency

response to about 120 MHz, so it wasn't possible to evaluate the 8753A's performance at higher drive

frequencies. My implementation works well with drive frequencies to at least 1

GHz.

Below: 1 GHz comb harmonics from KE5FX comb generator (FR-4 PCB version)

Microwave Performance

Microwave Performance

Unfortunately, the need for an affordable, reproducible PCB design may impose limits on performance in the bands above 2.4 GHz. Standard FR-4 material certainly becomes more lossy at these frequencies, although later tests (along with advice from people with more PCB experience) have suggested that insufficient trace-to-ground clearance on the top PCB layer is an even-greater contributor to high-frequency loss in my layout.

Compare the figure at left to the one obtained from the dead-bug prototype under identical conditions. The four-layer FR-4 board exhibits performance similar to that of the dead-bug prototype at 3 GHz and below, but those who are interested in harmonic generation to 10 GHz and beyond will want to use PCB materials (or, more likely, layout techniques) better suited to the job.

Sensitivity and Noise

It's important for a comb generator to work well at any input frequency in its range; significant "holes" in the spectrum at various combinations of input frequencies and power levels are undesirable. Consequently, my principal test procedure consisted of driving both the HP 8753A's comb generator and my own from a continuously-tunable HP 8640B signal generator, watching the output spectrum from DC to 2.5 GHz while smoothly varying both the drive frequency and power to compare the behavior of the two implementations. This methodology revealed that both the HP 8753A's comb generator circuit and mine are relatively indifferent to input signal levels.

Specifically, my circuit works well with input levels from approximately -5 to +15 dBm, while the output waveform of the HP 8753A's comb generator varies only slightly with input signals from -20 to +15 dBm. The additional gain of the HP 8753A's circuit comes at a price, though: it exhibits significantly more jitter (phase noise) than mine does. Ideally, the phase noise at harmonic N would be 20*log10(N) dB worse than that of the drive signal, but neither HP's generator nor mine approaches this theoretical limit.

Below: Phase-noise plot of FR-4 comb generator at 2.5 GHz compared to HP 8753A SRD source

Another interesting noise plot resulted from comparing the comb generator's output at 8 GHz to that of a high-quality

Frequency West brick and an experimental PLL (below).

At offsets beyond 40 kHz, the comb generator's phase-noise floor appears higher than the brick's, but overall this is a superb result considering the 8-GHz carrier frequency.

In reality, this plot says more about the limitations of the phase-noise test equipment than about those of the comb generator. Both of the phase-noise plots were taken with an HP 11729C carrier noise test set, a downconverting baseband-analysis instrument which is customarily driven by a low-noise HP 8662A signal generator. In the 8-GHz plot, though, I needed to use my HP 8662A to drive the comb generator itself, due to the 18-dB noise-multiplication penalty associated with measuring the N=8 harmonic. Consequently I had to use a much-noisier HP 8642B generator to drive the HP 11729C in that particular measurement. This fact accounts for most, if not all, of the rise in the comb generator's observed phase noise below 2 kHz. (For that matter, the comb generator's noise floor beyond 2 kHz is a good fit for the HP 8662A's phase-noise specifications, taking the 18-dB penalty into account.)

Another problem in characterizing comb-generator performance lies in the risk of overloading the spectrum analyzer due to the high peak-to-peak amplitude of the output waveform. I fell victim to this myself in my initial measurements of the HP 8753A's SRD generator module. It's not clear whether the effect I observed was due to first-mixer IMD or IF signal-path leakage, but either way, some of the comb harmonics were being suppressed at high signal levels... and I mistakenly concluded that my circuit was outperforming the HP design by several dB. I didn't catch the error until I went back much later to capture the phase-noise plots. Increasing the analyzer's front-end attenuation made the HP SRD generator look better (much to my chagrin!)

References

1. Micrometrics, Step Recovery Diode Application Note

2. Agilent Technologies AN 920, Harmonic Generation using Step Recovery Diodes and SRD Modules

3. Picosecond Pulse Labs, A New Breed of Comb Generators Featuring Low Phase Noise and Low Input

Power Microwave Journal, May 2006

5. Advanced Semiconductor, Inc., ASRD 800 Series Surface Mount Step Recovery Diode

6. ON Semiconductor, MC100EL16: 5V ECL Differential Receiver

7. Georgia Institute of Technology, The Propagation Group, ECL Design Guide, p. 7

8. Pulse Research Lab, ECL termination FAQ

9. Mini-Circuits Laboratories, GALI-5 data sheet

10. HP 8753A RF Network Analyzer, 300 kHz to 3 GHz

12. Frequency West brick documentation

13. Generation of short electrical pulses based on bipolar transistors Interesting article on SRD-like behavior in ordinary bipolar transistors. One implementation is here.

(English translation here with some further discussion on

EEVBlog.)